[ad_1]

Baseball is truly a game of goops and gunks. Clubbies prepare pearls with Lena Blackburne Baseball Rubbing Mud. Position players paste their bats with pine tar and pamper their gloves with leather conditioner. Trainers soothe sore muscles with Icy Hot or Tiger Balm, and coaches spray the field with foul streaks of tobacco juice. Between innings, players wolf down caramel-filled stroopwafels specially designed to replenish high-performance athletes while fans slather hot dogs with mustard, ketchup, relish, chili, and blindingly yellow nacho cheese sauce that is, in fact, none of those three things. And of course, pitchers have been known to secret everything from sunscreen to petroleum jelly to Spider Tack on their person. If it defies easy categorization as a solid or a liquid, there’s a place for it at the ballpark. Rosin sits somewhere in the middle. It’s powdered plant resin that sits on the mound inside not one but two cloth bags, but it doesn’t work its magic in that form. It requires a liquid to coax out its adhesive properties. The only approved liquid is sweat, for which a player might go to their hair or their forearm, but even then, there are limits. David Cone demonstrated the power of rosin after Max Scherzer’s ejection last April. With just a small amount of water and rosin, enough to create only the slightest discoloration on his fingers, Cone could create enough tack to make the baseball defy gravity.

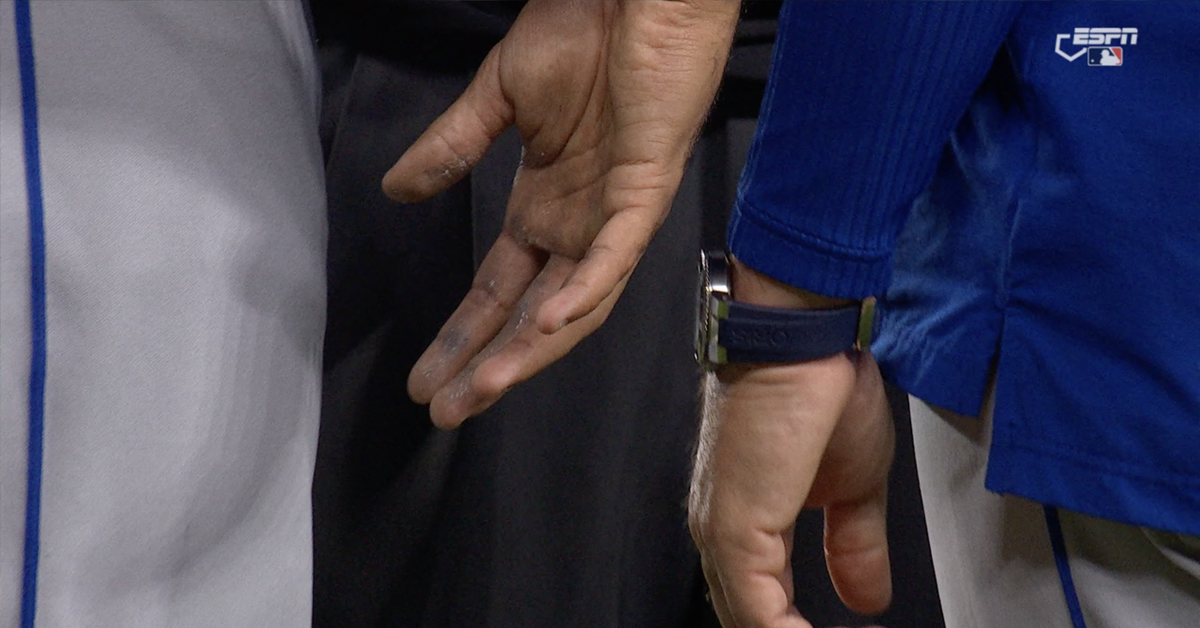

Keep mixing more and more sweat and rosin together – throw in some dirt for good measure or maybe throw in something a little stronger than sweat – and the concoction can cross the line and become too sticky, not to mention getting gloopy or grainy and starting to build up on the pitcher’s hand. After his ejection, Scherzer told reporters, “my hand was a little clumpy from the rosin.” If you saw the closeup of Edwin Díaz’s crusty right hand from ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball broadcast, you’ll understand what he meant. I have spent too much time staring at that closeup. I’m not sure what constitutes the right amount of time to stare at Díaz’s hand, but whatever it is, I have definitely exceeded it. I have brought the screenshot into Photoshop and zoomed in until the pixels swirled into an incomprehensible blur. I have played with the contrast and brightness, making whatever it is on his hand jump off the screen like the stripes of a clownfish under ultraviolet light. I have stared for long enough that I found myself no longer analyzing the accretion and discoloration and starting to notice the finer details: The piping on Díaz’s pants. The way the array of stadium lights hit his hand to create five distinct sets of shadows just in front of the piping. The pleating of the umpire’s pants. The ribbing on Mets manager Carlos Mendoza’s sleeve. The fact that Mendoza seems to be wearing a $2,500 Aquis made by Swiss watchmaker Oris. With the notable exception of Michael Pineda, who was nabbed 10 years ago thanks to an extremely visible patch of pine tar on his neck, I’m a bit surprised that we haven’t seen closeups like this before. Maybe it just took the extra cameras and relative objectivity of a national broadcast to make it happen. In the narrowest sense, the picture doesn’t change anything. Even if you hadn’t seen it, you had to imagine that Díaz’s hand looked and felt off in some way. And even if Díaz wasn’t using anything more than sweat, rosin, and dirt – and personally, I’m inclined to believe that he wasn’t – he clearly used enough that his hand crossed the line and merited an ejection. But in the context of baseball as a whole, this picture, which shows so clearly the substance on the hand, has changed the contours of the story. A little information is a dangerous thing, and the picture allows everyone to become an amateur sleuth. Since the league started cracking down on sticky stuff, the ejections have followed a set pattern. We see a short video clip of the umpire talking things over with the manager and the offending hurler, and then after the game we get three quotes: First, the pitcher insists that he was within the rules and tells the story of how he implored the umpires to believe him. “I just said I used the same thing as always,” said Díaz. “Rock rosin, sweat, and I put my hand on the dirt a little bit because I need to have some grip on the ball.” Second, the manager supports the player, throwing in some amateur materials science for good measure. “I got his back,” said Mendoza. “I truly believe what he was telling us. Edwin said it was rosin and sweat. The one thing that he did say was that it was humid so he had to go to it a lot more than earlier in the year when it was cold. Maybe that had something to do with it. I believe my player and I’ll stand by it.” Third, the umpire delivers a vanishingly brief quote to a pool reporter, resorting to poetry in order to express the delicate interplay of tackiness and human perception that determines the legality of a pitching hand. Quoth umpire Vic Carapazza: I told him it’s too stickyAnd we have to take action.I knewRight when I touched it. It wasWayTooSticky. It definitely wasn’trosin and sweat.We’ve checked thousands of these.I knowWhat that feeling is.This was very sticky. And then, having heard from all interested parties, we move on. But clearly, those quotes aren’t enough to really put a picture in your mind, because now that we have an actual picture, the set pattern has broken down. In this case, we got each kind of quote, but the visuals gave the story drama, along with enough staying power and enough specific questions that reporters were able to shake loose several more interesting details. For starters, Díaz said he protested his innocence by encouraging the umpires to smell his hand: “I just said, ‘Hey, you can check my hand, smell my hand.’ They didn’t smell anything.” I’m dying to know what scents he thought they would have been hunting for, and generous though his offer was, it’s hard to blame the umpires for declining it. “Never smell anything that someone is trying very hard to convince you to smell” is a rule that everyone learns at an early age. But what I love is that when you see the quote out of context, there’s some ambiguity. It’s not immediately clear whether Díaz is saying that the umpires refused the smell test altogether, or whether he’s saying that they did take a whiff and decided they didn’t smell anything untoward. Either way, as a last line of defense, “They didn’t smell anything” is hard to top. Carapazza’s line is equally evocative: “We’ve checked thousands of these.” These, meaning human hands. Not only is he correct, he’s underselling it. The number is actually in the hundreds of thousands. The umpires check those human hands at the top and bottom of every inning, which means that they get through a couple thousand every month. Since MLB instituted its tactical tactile tackiness enforcement policy in June of 2021, they’ve gently examined roughly 260,000 hands. They have found exactly eight wanting. We also learned practical things, because this story made Major League Baseball feel enough pressure to lift the veil just a little bit. According to Will Sammon, the umpires decide whether or not to give the pitchers a chance to wash their hands based on “if the umpire feels the player crossed a line with being sticky… In instances where a player has been allowed to wash up, the umpire felt something tacky but not sticky – they have been trained on the difference – or the situation involved discoloration or dirt without any tackiness.” It would seem that Díaz’s dread right hand, which bore the unhappy triad of stickiness, dirt, and discoloration, never stood a chance. From Andy Martino we learned how exactly Major League Baseball trained its umpires…

[ad_2]